A Lifetime of Learning Lends Itself to an Ultimate Get-Up Moment

Each year when a synchronized skater starts a new season, they are eager to find out the music they will skate to, the design of their costumes and the layout and choreography of their program. Feeling rejuvenated and ready to tackle the challenge and embrace change, skaters are excited for the journey that lies ahead. I was certainly one of those team members anxious to begin a new season, but I also had a stomach full of butterflies. There was a sense of fear that always stopped me in my tracks. It was a type of unsteadiness that not everyone around me felt; only I could describe what was racing through my head.

On day one of practice, my teammates and I stood at the door to the rink ready to warm-up. We’d skate up and down the ice performing cross rolls, back crossovers, rockers, counters and twizzles. We’d finish by stretching spirals and before we knew it, five minutes was up and our coach called us over to listen to our music. We stood quietly in a semi-circle, taking in the variation of melody that connected one piece of music to the next to blend our free skate together. Some teammates were stoic in expression, while others displayed enthusiasm as they connected well with the music. They could envision the program in their minds – the seamless transitions, the intricate footwork and the powerful skating in unison from one element to the next.

In a matter of time, I and nineteen others were learning the steps to what would soon be a program we’d practice weekly and sometimes daily. We went from learning the opening position to transitions and elements throughout the program. The choreographer would explain how we’d move from one element to the next. Sometimes, we’d go from one long line, then transition into a block with four lines of four, then switch to a parallel wheel, traveling down the ice with intricate steps, a variation of arm movements and simultaneously our heads would move in unison left to right on the beats of the music. I could sense my stomach turn, uncertain I’d able to keep up or that I wouldn’t be able to match my feet to the arm movements. My brain started to feel on overload, but I didn’t ever want the person next to me in line to know how uneasy I was feeling.

To a synchronized skater whose been practicing the sport for a decade and has a natural ability to pick up new choreography, this may seem like a piece of cake. They watch it once; they understand exactly what the choreographer is envisioning and confidently are ready to practice the section. To a synchronized skater like me, who struggled to retain and comprehend, it wasn’t so easy. While other girls on my teams were laughing, smiling and excited about the new season, my facial expression gave off a sense of fear, concern and anxiety.

It’s tough to be a synchronized skater; it’s even more challenging when it takes you twice as long to remember the steps. What I've stressed whenever sharing my story is that over time, retention and comprehension disabilities don’t go away. For example, if a person had ADHD as a kid, they still have ADHD as an adult. What was difficult at age 9 could still very well be difficult at age 19. The same struggles including absent-mindedness, difficulty focusing, forgetfulness, or short attention span whether it is in the classroom, on the ice or in the work place remains the same. There is no magic potion that turns a struggling student or athlete into a fast learner overnight. The only aspect that may change from adolescence to adulthood are the resources. Over time, people can learn various coping mechanisms and strategies to help them succeed.

When I came to tryouts for my first synchronized skating team in 1999, I seemed no different than anyone else on my team. I had passed the necessary requirements, I was happy to be there and eager to start my first season on a preliminary team. It didn't take long for my coaches to take note – I was looking at the skater’s feet next to me rather than focusing on myself. At age nine, it can be humiliating to admit needing help. Rather than raising my hand to say, “I don’t understand” my eyes drifted from looking up into the bleachers where parents were watching practice to the feet next to me for reassurance of the steps. I was confident the girl next to me was smarter and picked up the choreography quicker than I did. Instead of trusting myself, I trusted her. I spent years struggling with this wishing there was a way to fix this “problem.” Over time, I came to the realization that sometimes there are people who have to work just a little bit harder to keep up with the rest. I could have told my parents, “This is too hard, this is too challenging, I’m embarrassed, I think I could find a sport that doesn’t require this level of concentration,” but the ice always drew me in and it taught me to develop a work ethic that was like none other.

As years went on and I progressed in the sport, I developed the appropriate coping mechanisms to help me succeed. It required additional lessons, additional practice times, learning how to advocate for myself and ask for help. I'd video the step sequences and watch them at home and bring the video back to the rink the next day. It required using colored pencils to draw out a diagram of the step sequence and always having a notebook with blank pages handy. It was never easy and it always took going the extra mile, but when I got the steps, remembered them and was ready to confidently skate the program with my head up not looking down at the feet next to me, it was an indescribable sense of accomplishment.

There are times, we've put in a lot of hard work hoping the results turn out the way we've imagined. I knew that I could go to bed every night wishing my problems would go away, but the truth was they wouldn’t. I’ll always remember when a skating instructor or teacher at school would ask, “What is it that you don’t understand?” I often times felt that if I knew what it was that I was struggling with, I wouldn’t be standing there asking the question nor have a puzzled look on my face.

One of the greatest lessons I learned through overcoming adversity was that by continuing to work hard and put in the hours would get me what I always got: reward, a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. This has and always will be my get-up moment. What happens in one area of our life often times translates over to another area of your life. The mastery of choreography on the ice is one of the most beautiful arts our sport offers. Having the challenges that lay ahead of me at the beginning of each season was what made me stronger, confident and capable on and off the ice.

To learn more about U.S. Figure Skating's newest campaign Get Up visit: http://www.wegetup.com/

Share your stories on social media and let the world know that you're not alone; everyone struggles, it's about digging deep to find the reasons to keep going and get up!

Comments

Your article and journey are both beautiful and inspiring. Thanks for taking the time to share your story. I can't wait to have my 14 year old daughter read it. You put down on paper what so many probably feel, but just never say. Thanks! Jennifer

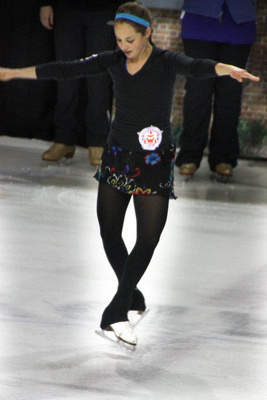

BTW...Great photos!!